Pre-season testing always manages to do two things at once: reveal just enough to spark genuine intrigue, and nowhere near enough to stop people from drawing definitive conclusions. The 2026 cars have barely logged meaningful mileage and yet the sport has already reached peak discourse, legality panic, washed narratives, nostalgia overload, reliability anxiety, sponsor resentment, and Adrian Newey once again designing something that looks like it shouldn’t exist.

Formula 1, exactly on schedule.

Aston Martin’s AMR26: Different by Design, Dangerous by Reputation

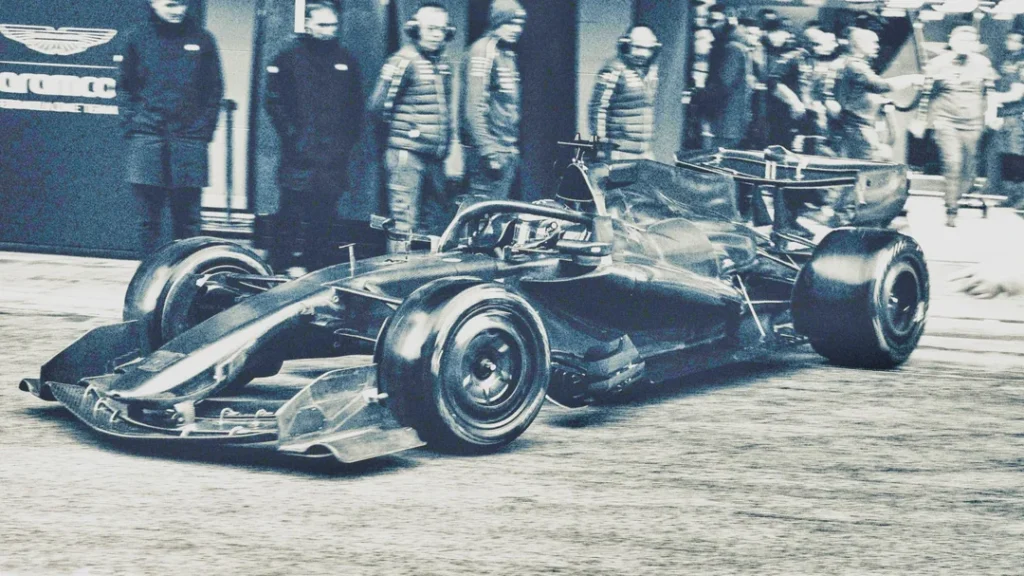

The AMR26 does not resemble the rest of the grid, and that alone has been enough to ignite half the internet.

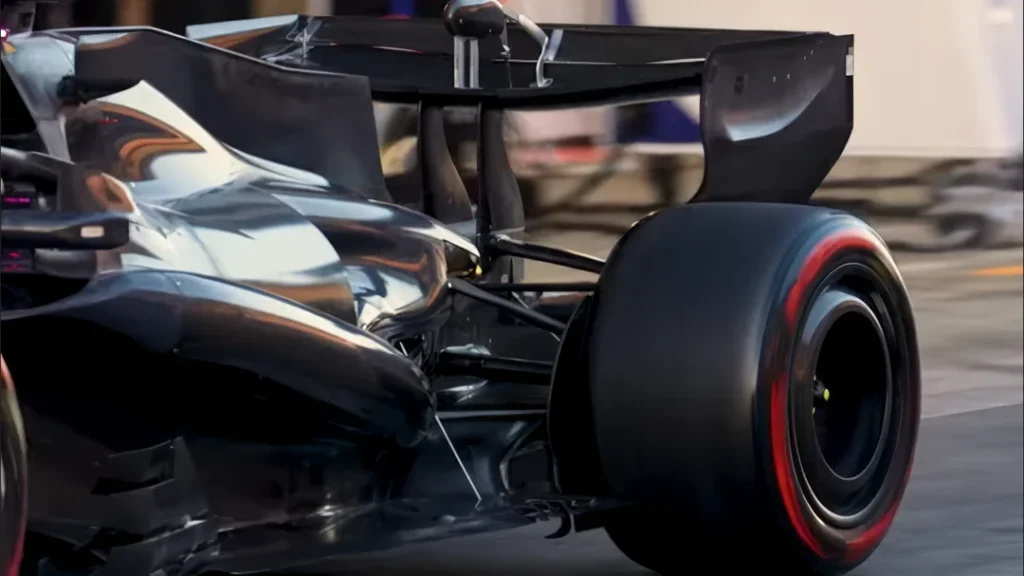

The bodywork is aggressively tight, almost shrink-wrapped, with carbon laid on so tightly it looks vacuum-formed rather than engineered. The sidepods appear extreme, unconventional, and immediately suspicious to anyone conditioned by recent regulation conformity. The reaction has been instant: either Aston Martin has found something genuinely clever, or they’ve pushed themselves into a corner they can’t escape.

The front suspension looks borderline antagonistic in its intent, the sort of design that exists purely to provoke rival technical directors. The rear suspension has gone even further, creating a situation where even experienced engineers admit they understand fragments of what they’re seeing but not the whole picture. Anti-squat theory has surfaced repeatedly, alongside the acknowledgement that in modern F1, suspension geometry increasingly exists to serve aero stability rather than mechanical grip.

The recurring conclusion, regardless of expertise level, has been consistent: it looks bold, it looks complicated, and it looks like something only Newey would sign off on.

That confidence is the point. Newey does not design safe cars. He designs cars that assume he’s right.

The Chassis–Engine Anxiety That Never Goes Away

As impressive as the AMR26’s concept appears, history has trained fans to flinch the moment a great chassis meets an uncertain power unit.

Memories of beautifully designed cars undermined by engine limitations resurface quickly. Comparisons to infamous ultra-tight packaging eras emerge just as fast. The fear is not irrational: Formula 1 has seen too many seasons where aerodynamic brilliance was rendered irrelevant by a power deficit that could not be solved mid-season.

This anxiety is magnified by Fernando Alonso’s presence. The sentiment is no longer about titles or sustained contention. It’s about closure. One more win. One more moment that doesn’t end in frustration or philosophical acceptance. The idea that Aston Martin could deliver an exceptional platform only to be held back by power is the kind of narrative F1 fans feel they’ve lived through too many times.

Hope remains high, but it is cautious, self-aware hope.

Reliability Returns to the Conversation Immediately

That caution intensified the moment the AMR26 stopped on track.

Lance Stroll’s breakdown and the resulting red flag were not met with shock so much as grim familiarity. The jokes came quickly, but underneath them was a real discussion about what reliability means in a new regulatory cycle.

Some see unpredictability as a necessary ingredient for compelling championships. Others argue reliability is part of what defines a constructor’s excellence. Both positions coexist uneasily, especially when memories of races lost to late failures still sting years later.

What’s clear is that reliability is once again going to shape narratives. Whether it decides championships or simply adds chaos will depend on how evenly it’s distributed across the grid.

Hamilton’s Spin and the Testing Overreaction Economy

Lewis Hamilton’s spin on Day 4 was a perfect demonstration of how little margin exists between analysis and absurdity during testing.

The reaction cycle was immediate: declarations of decline, exaggerated conclusions, and the usual refusal to acknowledge context. The reality is far more mundane. These cars are fundamentally different, with power delivery, energy management, and torque characteristics that demand adaptation even from the best drivers in the world.

Hamilton is also known for experimentation. While some drivers gravitate quickly toward optimal setups, others deliberately push beyond comfort to expose weaknesses. That approach has value, particularly when paired with a teammate focused on extracting maximum performance.

The incident itself was controlled, damage-free, and ultimately irrelevant. Testing is the correct place to find limits. Pretending otherwise misunderstands the entire purpose of these sessions.

Lando Norris, Number One, and the Recalibration of What a Champion Is

Seeing Lando Norris carry the number one still feels surreal, and that discomfort has forced a broader reflection on how modern F1 views champions.

Two decades of extended dominance cycles distorted expectations. Titles became synonymous with once-in-a-generation talent operating within near-perfect systems. That framing ignores the reality that championships are often won by drivers who peak at precisely the right time, commit to long-term development, and survive the volatility that defines Formula 1.

Norris did exactly that. He stayed. He absorbed pressure. He weathered team errors, lost points through no fault of his own, and responded to scrutiny with improvement rather than defensiveness. The result was not a flawless campaign, but a resilient one.

The backlash that followed was less about performance and more about tribalism. Dislike hardened into narratives, narratives into conspiracies. None of it changed the outcome.

The achievement stands. The legacy with McLaren is secure. The number one now belongs where the results placed it.

Straight-Line Speed, Spray, and the Shape of 2026 Racing

Early impressions of the 2026 cars suggest a shift in sensation rather than outright pace. Straight-line acceleration feels sharper. Top speeds arrive faster. Active aero is doing exactly what it was designed to do: reduce drag aggressively and return straight-line spectacle to the sport.

Cornering speeds may be lower, but the tradeoff appears intentional. The cars feel violent in acceleration, with torque that punishes hesitation and rewards precision.

Wet running has reopened a long-standing debate about spray. Early visuals suggest less lingering mist, but conditions vary too much for certainty. The key question is not the height of the spray plume, but how long it hangs in the air once thrown up. Early signs are mildly encouraging, though no one expects miracles when the full grid is released onto a soaked track.

The artificial rain discussion resurfaced, predictably, and collapsed under the weight of its own implications. The sport can accept danger inherent to racing; manufacturing it deliberately is another matter entirely.

Mileage, Meaning, and the Only Reliable Indicator in Testing

By the end of Day 4, one metric stood out more than lap times: laps completed.

Mercedes and Ferrari logged significant mileage. Reliability appeared solid. That alone was enough to inspire cautious optimism. At the same time, experience tempers excitement. Reliability without performance has been seen before. Speed without reliability too.

RB’s power unit showed promise, though torque-heavy characteristics suggest mistakes will be punished sharply this season. Smaller tires and aggressive energy deployment hint at an increase in snaps, spins, and qualifying incidents once the cars are pushed in anger.

Aston Martin, characteristically, remains quiet.

Where This Actually Leaves Us

Nothing is settled. Everything is speculated.

The AMR26 could be inspired or overreached.

The 2026 regulations could rebalance racing or simply reshuffle problems.

Reliability could define championships, or steal them.

Testing has already delivered exactly what it always does: enough information to argue endlessly, and nowhere near enough to be right.