Three days into 2026 pre-season testing at the Bahrain International Circuit, and Formula 1 finds itself in a strange place.

The cars are slower. The drivers are uneasy. The engineers are deeply involved in what used to be instinctive moments. And the paddock narrative is swinging wildly between “everyone’s sandbagging” and “this might be a disaster.”

Let’s unpack what we’ve actually learned, and why the tension feels different this time.

Flat Out… With Formula 3 Power

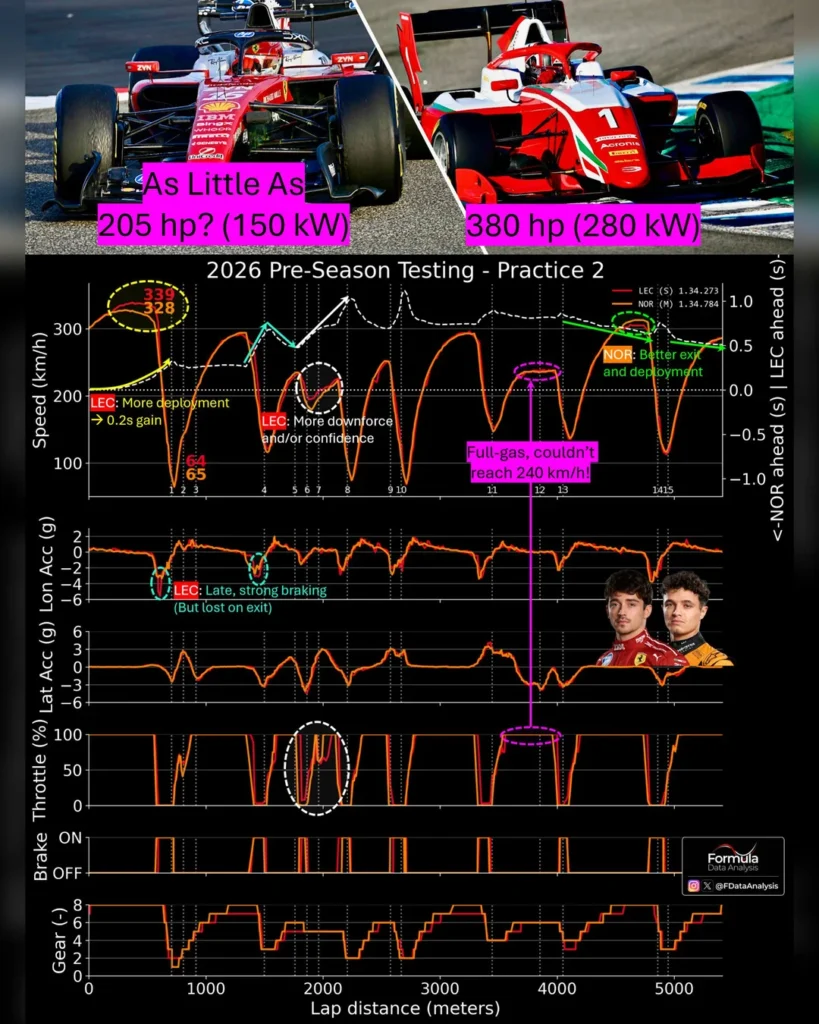

The most surreal data point from Bahrain came at Turn 12.

Charles Leclerc and Lando Norris were full throttle for roughly 300 meters, and yet their cars could not exceed 240 km/h. Under the 2026 regulations, the ERS is allowed to generate negative power, up to -250 kW, even when the driver is flat on the throttle. With internal combustion output sitting around 400 kW, that means instantaneous power can drop to roughly 150 kW.

That’s about half the output of a Formula 3 car.

The implication is stark: a driver can be flat out, but the software determines whether the car delivers 200 horsepower or 1000. Engineers now control instantaneous deployment to a degree that fundamentally reshapes what “flat out” even means.

Energy harvesting isn’t new to F1. But what’s different now is scale. Hybrid deployment accounts for roughly 50% of total output, and with the removal of the MGU-H and no front axle regeneration, harvesting capacity is constrained. That makes overtaking and race pace a delicate energy economy.

If you push to pass, you pay for it later.

“It’s Not the Most Enjoyable Car”

Charles Leclerc was blunt:

“I cannot lie, it’s not the most enjoyable car I’ve driven… I’m a bit more skeptical about overtaking.”

Fernando Alonso went even further, noting they’re going 50 km/h slower through certain corners than before, purely to manage energy. He even joked that the team chef could drive these cars.

Oscar Piastri described lifting on straights, something that goes against every racing instinct developed over 15 years. Starts, he said, could resemble F2 anti-stall scenarios where a minor mistake costs six or seven positions instead of five meters.

The theme across Alonso, Leclerc, Piastri, Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen is consistent: physically manageable, intellectually complicated.

That’s not necessarily fatal. But it is different, and different is rarely comfortable.

Overtaking: Cat and Mouse, or Just Processions?

Andrea Stella warned that following and overtaking have proven “extremely difficult” in testing. With equal drag and equal power when following, the old DRS imbalance is gone, but so too may be the overtaking window.

Drivers now must harvest to deploy. And if both cars have similar energy states, the advantage cancels out.

The paddock fear crystallized around two possible scenarios:

- A: Overtakes become trivial and meaningless

- B: Everyone manages 95% of the race and waits for rare energy windows

Right now, B feels more likely.

The energy tradeoff is brutal: deploy too much and you crawl in the final laps. Save too much and you never pass. Formula E comparisons are inevitable, without the dense urban chaos to compensate.

The Front Axle Question

Repeatedly, the conversation circled back to one technical omission: front axle regeneration.

LMP1 machinery like the Audi R18 e-tron quattro harvested from the front, allowing balanced deployment. In F1’s 2026 package, regen is limited to the rear. With 90% of braking force typically at the front axle, that’s a significant lost opportunity.

The removal of the MGU-H compounds the issue. Without it, turbo spooling becomes a factor again, particularly at starts.

Which leads to the next political flashpoint.

Ferrari, Turbo Lag, and a Brewing Political Fight

Ferrari reportedly identified start procedure risks over a year ago: without the MGU-H keeping the turbo spooled, revving in neutral doesn’t generate enough exhaust flow to eliminate lag. They built their power unit architecture accordingly, potentially retaining a smaller turbo concept.

Other manufacturers dismissed the concern.

Now, with multiple practice starts appearing awkward or delayed, calls for start procedure changes are resurfacing, framed as safety concerns.

The dynamic is obvious: Ferrari adapted. Others may not have. And any rule change now could erase an engineered advantage.

The FIA has previously considered reducing race deployment from 350 kW to 200 kW (qualifying unchanged) to ease energy constraints. It was rejected. But officials have left the door open to revisiting it if racing quality suffers.

Aston Martin: Hard Mode Activated

If the regulatory anxiety is abstract, Aston Martin’s situation is painfully visible.

Reports of 4-second deficits. 320 km/h top speeds on qualifying simulations, nearly 20 km/h down on rivals. Comparisons to early McLaren-Honda struggles and 2010 backmarkers are resurfacing.

Lance Stroll’s garage reaction looked less like sandbagging and more like frustration. Alonso has acknowledged cooling and vibration issues tied to the Honda power unit at high revs.

Adrian Newey, now team principal, was photographed kneeling beside the car, a symbolic image that sparked both optimism and doubt. Engineering brilliance does not automatically translate to management success. Hundreds of synchronized decisions now determine performance, not one genius sketchbook.

And unlike the front-running teams, few believe Aston Martin are hiding pace.

Who’s Actually Fast?

Public positioning has turned into a logic puzzle:

- Red Bull claim Ferrari, Mercedes and McLaren are faster.

- Mercedes say Red Bull are faster.

- Ferrari say Red Bull and Mercedes are faster.

- McLaren say they’re behind Ferrari.

Add in optimistic rookie Isack Hadjar believing the RB22 can win races, and you get a preseason narrative kaleidoscope.

Some internal analyses attempt to quantify the “performance accountability” of these statements, but the simpler conclusion stands: Mercedes and Red Bull are viewed most consistently as front runners, even if no one wants to say it outright.

Sandbags are assumed. Until Australia Q1 proves otherwise.

Slower, But Does That Matter?

Race simulations are roughly 1.5–2 seconds slower than early 2022 benchmarks. Qualifying pace appears closer.

F1 has always been artificially constrained by regulation. Engine displacement limits date back nearly a century. Ground effect has been banned and revived. Active suspension, grooved tires, planks, all tools to cap speed for safety.

The question isn’t whether the cars are slower.

It’s whether the racing improves.

If sacrificing 1-2 seconds per lap yields better wheel-to-wheel action, most would accept it. But if management replaces competition, if flat throttle becomes a software suggestion, the philosophical debate intensifies.

The Real Test

Testing headlines from outlets like The Race capture the uncertainty:

- McLaren and Mercedes probing Red Bull’s advantage

- Red Bull downplaying expectations

- Aston Martin already on the back foot

But preseason noise is cheap.

The real reveal comes at Melbourne.

Until then, the paddock oscillates between panic and patience. Some call it overcooked hybrid complexity. Others argue F1 has always been engineering-first. Some demand V10 nostalgia. Others insist this is simply evolution.

Right now, one thing is clear:

The 2026 cars are redefining what “full throttle” means.

Whether that produces a masterpiece or a procession remains to be seen.