Pre-season testing is supposed to be about lap times, correlation runs, and cautious optimism. Instead, 2026 has opened with compression ratios, unofficial meetings without Mercedes, blown diffusers, turbo-lag panic, and a full-blown metaphysical debate about whether the Ferrari Curse and Kardashian Curse cancel each other out.

Welcome to Formula 1.

The Compression Ratio War

The headline conflict is clear: Mercedes’ 2026 power unit has passed FIA verification under the current geometric compression ratio test, 16:1, measured after heating the engine to 115°C and dismantling it at roughly 95°C. Within tolerance. Legal under the test.

But legality under test conditions is not the same thing as legality in operation, and that distinction has lit the paddock on fire.

Rival manufacturers, Ferrari, Honda, Audi, and Red Bull Powertrains, questioned whether the engine remains compliant “at all times during the event,” as the regulations state. The controversy spiraled into theories about micro-chambers, Helmholtz resonance effects, tiny connecting channels that become “dead zones” at high frequency, and whether Mercedes had effectively created a geometric 16:1 engine that behaves like something closer to 18:1 when running.

Some argued this is classic loophole exploitation, engineering creativity living in the grey area between intent and wording. Others called it something closer to evading enforcement: if the rule says 16:1 at all times, then passing a cold (or cooling) test doesn’t automatically settle the matter.

The nuance matters. Ferrari in 2019 was deemed to have actively defeated the measurement system. Here, Mercedes built an engine that complies with the test as defined in the regulations. The FIA is now changing the testing method, raising the representative operating temperature to 130°C from the Hungarian GP onward, rather than rewriting the compression limit itself.

That distinction is at the heart of the debate.

If Mercedes had been clearly illegal, they would be in the room defending themselves. Instead, there were unofficial meetings of power unit manufacturers without Mercedes at the table, a detail that only fueled speculation. Some see that as anti-Mercedes coordination. Others interpret it as the FIA signaling that the design is legal this season and that any future adjustments are procedural, not punitive.

Either way, the practical outcome is compromise: Mercedes and its customer teams, McLaren, Williams, and Alpine, can run the current specification until Hungary. After that, the new test applies for the final 11 races.

Predictably, the reaction splits into two camps:

- Mid-season changes compromise sporting integrity.

- Doing nothing risks another era of dominance.

With a third of the grid running Mercedes hardware, an immediate ban would effectively remove four teams. With manufacturing lead times of four to five months and homologation deadlines looming, the FIA boxed itself into a corner.

The result? A classic FIA solution: neither full endorsement nor full rejection. A clumsy middle path.

Is It a Loophole — or Cheating?

The debate has become philosophical.

One view: a loophole is exploiting an unanticipated gap in measurement. Mercedes complied with the written test. That’s F1 engineering.

The counterview: the rule says 16:1 at all times. Designing an engine that exceeds it in operation but passes the test is like speeding on Tuesdays because police don’t patrol then. That’s not a loophole, that’s exploiting enforcement limitations.

The FIA’s response, amending testing conditions, suggests this is an interpretation issue, not outright illegality. But by moving to a 130°C representative temperature test, they are implicitly acknowledging that ambient-based verification was insufficient.

The unresolved question: will the hotter test even change much?

Skepticism is high. Some see this as another TD39 or flexi-wing moment, enormous drama, minimal performance shift. Others foresee chaos if a random third team fails the new thermal criteria after months of scrutiny aimed at Mercedes.

“Schrödinger’s compression” might be the most accurate label for now.

Turbo Lag Panic and the Anti-Traction-Control Brigade

While compression ratios dominate the politics, the on-track discourse has centered on turbo lag and the removal of the MGU-H.

Some teams raised “safety concerns” about the new standing start procedure. Lewis Hamilton, Valtteri Bottas, and Max Verstappen dismissed them outright. The subtext was unmistakable: if you feel unsafe, start from the pit lane.

The suggestion that electric boost be allowed below 50 km/h, as in WEC Hypercars, was quickly countered. Under current regulations (C5.2.12), the MGU-K may only deploy after 50 km/h during a standing start. Allowing electric torque at low speeds risks reintroducing traction control by stealth, and traction control remains banned.

That triggered a broader philosophical split:

- No TC preserves driver skill, especially in wet conditions.

- TC would reduce errors and compress performance gaps.

History was invoked: 2008 post-TC ban, 1994’s active suspension removal, the standard ECU introduction to police “fuzzy” ignition tricks. The conclusion from many corners was consistent: driver-controlled throttle application is fundamental to F1’s identity.

The turbo lag hysteria itself drew skepticism. Claims of “10-second spool-up” were met with ridicule, 1980s 1400hp monsters spooled in around 1.5 seconds. Unless the turbo is “the size of an airplane engine,” that narrative doesn’t hold.

The more measured take: whoever minimizes lag best wins. Media noise aside, this is engineering competition doing what it has always done.

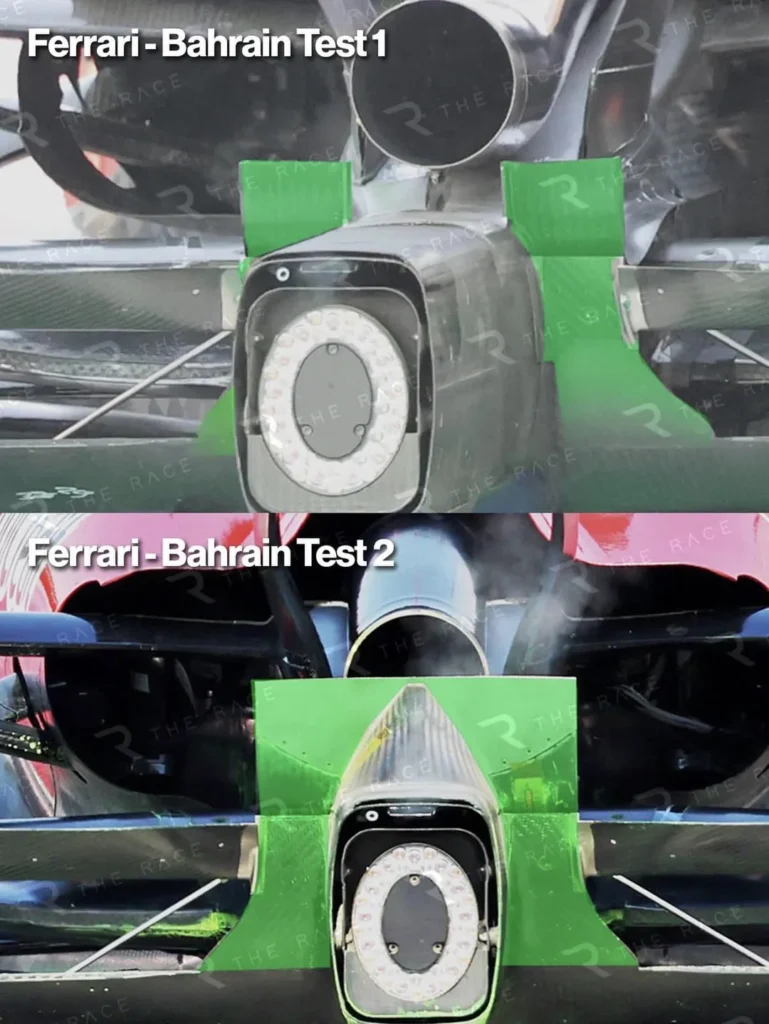

Ferrari’s Wing and the Return of the Blown Diffuser Debate

If Mercedes represents engine ingenuity, Ferrari has stirred aerodynamic intrigue.

A small winglet positioned ahead of the exhaust has sparked widespread analysis. Approved by the FIA prior to use, the element appears to energize airflow over the diffuser, effectively increasing rear downforce by accelerating hot exhaust gases across its upper surface.

Is it a blown diffuser? Not in the old sense. The regulations restrict exhaust positioning, but they do not ban “blown diffusers” by name. If Ferrari has designed its rear packaging, differential placement included — to legally exploit this narrow window, that’s conceptual integration, not an add-on trick.

Estimates range wildly, from negligible to 0.15–0.20 seconds per lap. Whether that’s optimism or “hopium” remains to be seen.

The familiar pattern emerges again: innovation first, outrage second, clarification third.

The 2026 Cars: Less Planted, More Alive

Amid the political storm, Martin Brundle offered a grounded observation: the 2026 cars move around more. They are less reliant on massive downforce and more sensitive, with “gremlins” still to be ironed out. He suggested we may even regain iconic flat-out corners like Copse and Eau Rouge.

That comment cut through the noise.

The obsession with lap times ignores how those times are achieved. Slightly slower cars that demand more from drivers can improve spectacle. Less planted entries, more visible correction, more opportunity for mistakes, that’s not regression. It’s differentiation.

The real concern is overtaking. Will racing devolve into predictable battery “yo-yo” swaps on straights, or will energy management create layered strategic battles where committing to a pass carries genuine consequence?

If drivers must manage battery deployment, defend smartly, and avoid over-commitment, that’s not randomness, it’s a new game.

The danger is predictability. The opportunity is skill differentiation.

And Then There’s Ferrari, and Lewis

Into all of this steps Lewis Hamilton, now publicly stating he feels “more connected” to the 2026 Ferrari and is “really excited” for the season.

Predictably, the internet has framed this in metaphysical terms: does the Ferrari Curse cancel the Kardashian Curse, or do they multiply?

Beneath the memes is a legitimate sporting question: can a 41-year-old Hamilton beat Charles Leclerc across a season?

One side argues Leclerc is in his prime, one of the most consistent drivers on the grid, unfairly defined by a single France crash meme. The other reminds everyone that this is seven-time world champion Lewis Hamilton, and peak Lewis was on a different tier entirely.

The debate ultimately hinges on machinery. If Ferrari produces a sustained title-contending car, both drivers will have the opportunity to prove consistency under pressure. That, more than pre-season lap times, will define 2026.

For now, the mood among Ferrari supporters oscillates between guarded optimism and emotional self-preservation.

“Race by race” may be the healthiest stance available.

What 2026 Already Tells Us

Before a single race has started, 2026 has delivered:

- A regulatory ambiguity turned political standoff.

- An engine test rewritten mid-season.

- A potential blown-diffuser revival.

- Turbo lag fear campaigns.

- And a philosophical war over what “pinnacle of motorsport” actually means.

If nothing else, one truth is clear:

F1 remains as much a political drama and engineering chess match as it is a racing series.

And if the first green lights go out in Melbourne and none of this changes the competitive order at all?

That might be the funniest outcome of all.