The early story of Formula 1’s 2026 regulation cycle is not one of clean narratives or obvious winners. Instead, it’s a grid-wide exercise in interpretation, risk tolerance, and controlled chaos, spanning liveries, weight declarations, missed tests, active aero philosophies, and a growing sense that nobody truly knows what they’re looking at yet.

Williams: Branding Momentum Meets Technical Reality

Williams’ FW48 reveal immediately sparked discussion for reasons that had little to do with lap time. The livery leaned hard into identity: layers of blue, an overwhelming number of sponsors, and a Duracell battery placement that continues to be regarded as some of the most effective branding on the grid. The small “Carlos →” markings tucked beneath the Duracell on the shoulders of the car became an instant talking point, subtle enough to miss at first glance, clever enough to reward a second look.

That same sponsor density, however, triggered debate about coherence. Some saw a confident, financially healthy team embracing its commercial reality. Others felt parts of the livery, most notably the Barclays blue on the sidepod and the roulette-style wheel covers, looked bolted on rather than integrated, with legibility and balance sacrificed for late-stage additions. The permanent wheel covers, in particular, drew criticism for feeling tacky and visually disconnected from the rest of the design.

The team’s apparel launch reinforced that tension. Jackets and shirts were widely described as looking less like design pieces and more like walking sponsor lists, with pricing that intensified backlash once material quality came into question. What worked on the car did not necessarily translate to something people wanted to wear, reopening the familiar debate about modern F1 merch becoming billboard-first and fan-second.

The Weight Question No One Can Answer (Yet)

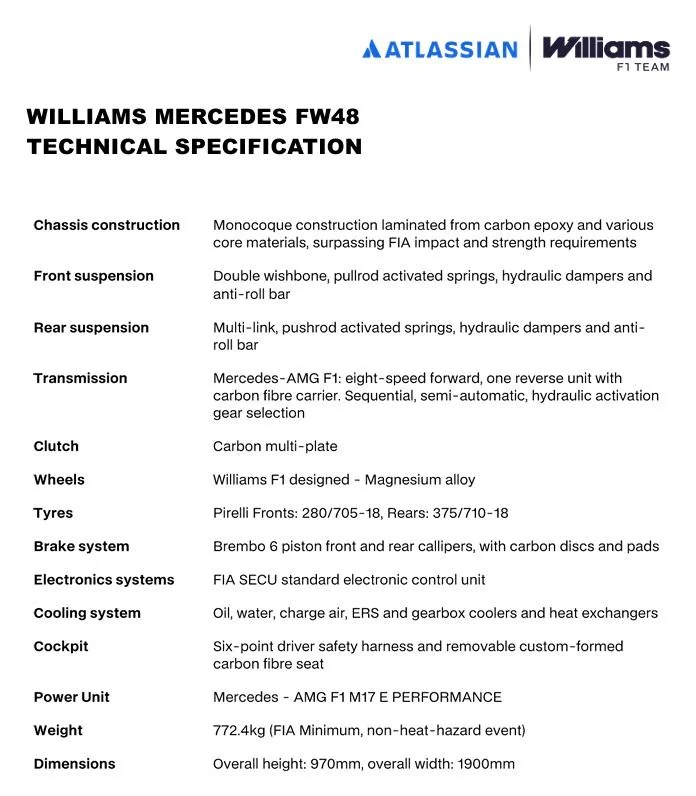

Williams listing the FW48 at 772.4 kg ignited a much broader conversation, less about Williams specifically and more about whether any published 2026 weight numbers currently mean anything at all.

Ferrari and Haas were cited at 770 kg. Mercedes at 772 kg. But the more the discussion unfolded, the clearer it became that teams are likely publishing different interpretations of the regulations: some referencing race-session minimums, others qualifying limits, all of them incorporating tyre mass that has not yet been officially published by the FIA.

With tires now treated separately, minimum weight is no longer a single fixed number. The baseline sits at 724 kg plus a nominal tire mass that will only be finalized after testing, with an additional 2 kg allowance in qualifying. That makes Williams’ number consistent with a qualifying limit rather than a definitive statement of competitiveness, or overweight inefficiency.

Spec sheets, it was noted, are not scrutineering documents. Teams have no incentive to admit being overweight, but plenty of incentive to publish numbers that look respectable, buy time, or muddy competitive comparisons. In that sense, weight has become less a data point and more a psychological one.

Missing Barcelona: Gamble or Self-Inflicted Wound?

Williams’ absence from the Barcelona test was framed internally as a calculated risk: delaying final design commitment to avoid locking in an outdated car, mirroring approaches used by teams like McLaren. Externally, reaction was far less forgiving.

The loss was not symbolic. It was three of nine total test days. Hundreds of laps. Critical early correlation data. While the term “shakedown” was used liberally, few accepted that label at face value. With other teams logging 400-500 laps, Williams now enters Bahrain needing to validate simulation tools while competitors move on to optimization.

Supporters argued the delay stemmed from ambition rather than dysfunction, a team pushing margins instead of merely showing up. Critics countered that basic operational readiness is non-negotiable, especially for a team still rebuilding. Under the cost cap, many questioned whether failing to field an earlier-spec car truly preserved resources, or simply reflected limited production capacity.

What emerged was not consensus, but a conditional verdict: if the car is fast, the gamble looks inspired. If it isn’t, there will be nowhere to hide.

Qualifying in 2026: Designed for Disorder

Beyond Williams, the 2026 regulations are already reshaping expectations around qualifying. Additional cars on track, battery-dependent outlaps, stricter energy management, and traffic constraints have raised concerns about randomness, particularly at circuits like Monza, Monaco, and Austria.

The core fear is not difficulty, but unfairness. Outlaps now demand precise energy conservation while still warming tires and avoiding impeding faster cars. A single forced acceleration or evasive move could cost half a second on a flying lap. That margin is existential in modern F1.

Some welcomed the complexity as a skill separator. Others warned it risks turning qualifying into a lottery, where perfect execution can still be undone by circumstances outside a driver’s control. Proposed fixes ranged from moving timing lines to before pit entry, to harsher impeding penalties modeled on IndyCar’s system.

Whether chaos becomes a feature or a flaw may depend on how consistently it strikes, and how quickly teams learn to weaponize it.

Active Aero: Philosophy Over Fashion

Active rear wing designs have already diverged. Ferrari’s approach favors maximum drag reduction, while Alpine’s mechanism prioritizes airflow stability around the beam wing and diffuser, even at the cost of peak straight-line efficiency.

The debate quickly shifted from aesthetics to engineering fundamentals: failure states, spring loading, aerodynamic forces, and regulatory compliance. While internet hypotheticals imagined catastrophic scenarios, the prevailing view was simple, any legal system must default to corner mode in failure conditions, regardless of how the wing moves.

What remains unresolved is advantage. Ferrari-style systems promise top speed. Alpine-style systems suggest cornering consistency. Without CFD data, speculation remains just that, but the divergence itself hints that 2026 may reward philosophical alignment as much as raw innovation.

Newey, Aston Martin, and Expectation Management

If any team embodies the tension between hype and reality, it is Aston Martin. Adrian Newey has been unusually open about starting behind: delayed wind tunnel readiness, compressed development timelines, and a base car that prioritizes fundamentals over visible complexity.

That transparency clashed sharply with early reactions to the AMR26, which many had praised as intricate and highly developed. Newey’s explanation reframed it as intentionally incomplete, a platform designed for aggressive iteration once correlation tools stabilize.

Some saw echoes of McLaren’s resurgence. Others, reminders of Aston’s recent struggles with upgrades and consistency. What Newey appears to be doing, deliberately, is lowering expectations while emphasizing adaptability. In a regulation cycle defined by copy-and-evolve dynamics, that may prove more valuable than arriving early with a finished-looking car.

No One Knows Yet, and That’s the Point

Across Williams, Aston Martin, Alpine, Ferrari, and beyond, a common thread is emerging: certainty is an illusion right now. Liveries lie. Spec sheets mislead. Visible complexity means little without correlation. And every team is balancing when to commit against when to wait.

The 2026 season is shaping up not as a sprint out of the gate, but as a long game of interpretation, patience, and reaction speed. Some teams will flinch early. Others will arrive late. And a few may discover that adaptability, not boldness, is the real competitive edge.

For now, all anyone can do is watch, argue, and wait for the first lap in Australia, where, as always, the rest stops mattering.